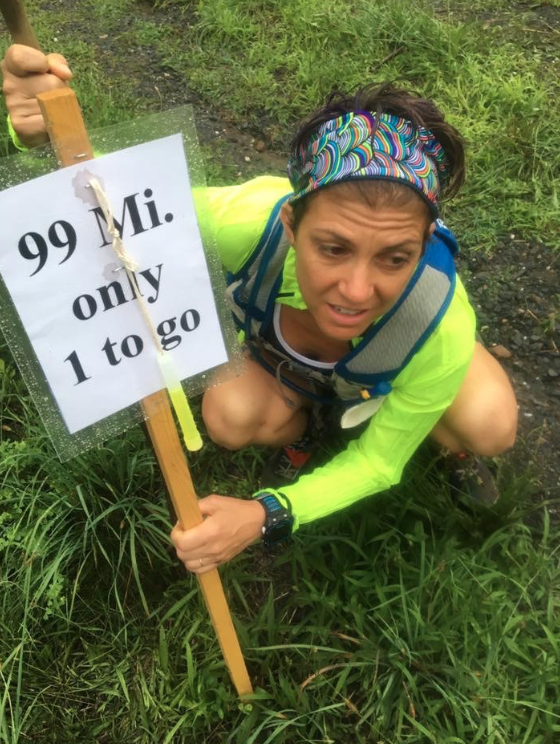

It was July 2016, and I wasn’t feeling right. I had just finished a 100-mile race, but it felt awful (well, more horrible than it usually does). Most of my training leading into that race was subpar as well.

I experienced months of extreme fatigue, so bad that I was falling asleep at red lights. My performance was declining, and my heart rate was behaving oddly at rest and under load. I had a growing suspicion that something was wrong, and after that race, I acknowledged what was happening.

I was overtrained and under-recovered.

I had several years of substantial training loads from 2014 to 2016. It was a great run in my racing career, but it was taking a toll – especially when coupled with my increasing professional responsibilities at that time, with growing a business, and working full-time as a professor.

It was too much, and my body was revolting against the stress.

To heal myself, I took the month of August off from training. I still moved my body, but I removed all structure from my training. I went on fun hikes, easy swims, and meandering bikes. I tightened up my nutrition and focused on good sleep. By mid-September, I was starting to feel like myself again, and I knew I had found my way to the other side.

I was lucky. My symptoms had not progressed to full-blown overtraining syndrome, but I was flirting with the edge of it.

Overtraining results in a pattern of fatigue, under-performance, frequent illness, or burnout that occurs without other identifiable medical causes. Ultimately, we can find ourselves approaching this state when our training load-to-rest ratio gets out of whack. In this article, we’ll review what overtraining is, the symptoms, and how you can prevent it.

Overtraining or Overreaching?

Let’s start with a refresher on how training works. We apply a progressive overload of a training stimulus, which, in the short term, fatigues the body. This is known as overreaching. We overreach to force the body to make adaptations and create new fitness. For example, if you run 60 minutes one week, your plan may progressively overload to 70 minutes in the following week. Another example may be progressing a series of 5-minute hard intervals to 6 minutes. In either case, we had a greater training stimulus in terms of intensity or duration, and we push the body to reach for a new edge.

Controlled overreaching is a good thing. But, as training increases, so does fatigue, and performance will decline unless we allow for appropriate recovery. Daily, this recovery comes in the form of sleep, eating nutrient-dense foods, mobility work, and myofascial release (such as foam rolling or massage). Across weeks and months, this recovery comes in the form of easy days, rest days, and reduced volume weeks. At the end of a long season, we need deep recovery, which is why your post-season downtime is so important!

Recovery gives the body the time it needs to adapt to the periods of overreaching, in a process known as supercompensation. Thanks to supercompensation, our performance will improve after the recovery has completed.

Symptoms of Overtraining

Cutting recovery will lead to performance plateaus or declines. It’s not if, it is when. Maybe you can get away with it for a while, but eventually, the breakdown of training will create issues.

When the symptoms first present, this is usually the start of what is called non-functional overreaching. The term non-functional connotes that the body is no longer adapting to the training and making performance improvements. If we allow for extended recovery, up to 2 weeks, we can usually pop out of this state. But, if we keep pushing and don’t honor the rest, we can end up with overtraining syndrome, which is a much more persistent condition, and can take months (or years!) to fix.

Overtraining is not easy to diagnose because in our day-to-day training, we may experience any one or more of the symptoms below. As we discussed in last week’s newsletter article on progressive overload and training dials, training is meant to break us down. So, in the short term, of course, we feel fatigue!

However, non-functional overreaching or overtraining leads to an extended pattern of symptoms that don’t dissipate after we get rest. These symptoms include:

- Under-performance – slower pacing, lower power numbers – relative to HR and RPE

- Excessive fatigue and generally feeling unrefreshed upon waking

- Heavy muscles or muscles that are sore without a clear reason (e.g., you do your normal training and feel sore)

- Mood changes (esp. depression, anxiety, or apathy)

- Sleep disturbances (difficulty falling asleep, nightmares, waking up frequently, or waking unrefreshed

- Loss of appetite and/or weight loss

- Changes in HR rhythms (may be abnormally high at first, and then can progress to be abnormally low as overtraining progresses without ample recovery)

- Frequent sickness, especially upper respiratory infections

- A low testosterone to cortisol ratio, and higher overall levels of cortisol and noradrenaline (you would need to ascertain this through a blood test; some of these markers can be identified with the Inside Tracker tests)

Keep It Functional: Invest in Recovery

Ultimately, our ability to absorb training in a functional manner is tied to how well we recover. How well we recover is tied not only to rest from training but also to the total stress in our lives. So, if you are experiencing a particularly stressful period, this will impact your typical recovery time.

For example, you may normally be able to handle a 10-hour training week. However, let’s say for the past 2 weeks, work has been incredibly stressful. Now, you aren’t recovering like you normally do. So, it is important to share with your coach when life stressors are heating up. If you are self-coaching, give yourself some grace to add in a bit more recovery during highly stressful periods.

Remember: stress is stress regardless of the source: personal, professional, or athletic. The body needs to balance this stress to avoid burnout. In my case, I didn’t heed the impact of professional stress at that time – and I paid for it. To prevent overtraining, invest in your recovery.

If you feel like you are suffering from some level of non-functional overreaching or overtraining, the most important thing you can do is adapt your training immediately to allow for more recovery, which may mean rest days, reduced load weeks, or easy training sessions. Recovery also requires ample SLEEP.

If you do train, the efforts should always be aerobic in nature – in your Zone 1 or zone 2 range, and keep them short in duration, starting off with as little as 5 to 10 minutes per day, and not working out more than 30-45 minutes per day until symptoms dissipate significantly. Drop the structure until you feel better!

When we are heating up our edges, it is normal to get a little close to the fire. When that happens, take a step back and allow the recovery process to do its work. Your future performance is counting on it!

Don’t let overtraining hold you back. Work with a No Limits Endurance coach to train smarter, recover better, and reach your peak performance—start today.